|

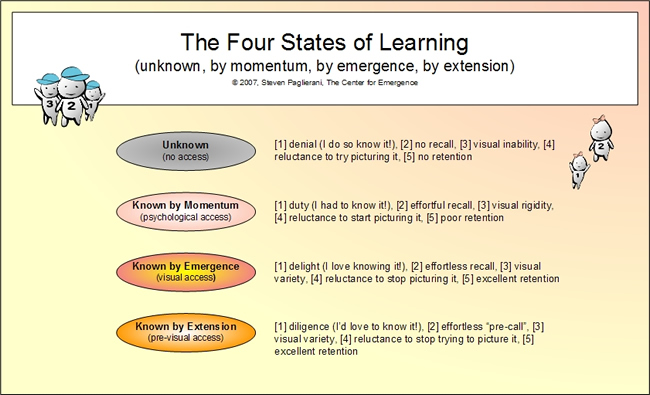

Have you ever tried to learn something new only to fail again and again? If so, did you feel positively challenged by what you were struggling to learn or did you see these struggles as proof you are in some way intellectually less than others? In truth, we all struggle when learning new things. Especially young children. So what makes it so hard for us to learn new things? Is learning really this hard? Or is there something going on here we don’t usually see, something we might make better especially for our children? These questions are where we will begin in this, the opening chapter of What Kills the Love of Learning. Chapter OneLearning Greek - What Makes it So Hard? Studying GreekFor more than a year now, I've been teaching myself Greek; to read, write, and speak it; the whole enchilada. So let me ask you. Have you ever taken a close look at the Greek alphabet. What Greeks call, the "alphavito?" If you have, I'm sure you probably had the same reaction I had at first. Oh, boy! I'll never be able to learn this stuff. So have I managed to learn any of it? Before I answer, let me first explain why I chose to study Greek. I chose to study it so as to experience what it felt like for me not know how to speak or read. In other words, I wanted to experience life in a preverbal state, something like the sate in which children live for their first four years of life. Why Greek though? I figured the Greek language, with its alien looking alphabet and oddly combined consonant sounds, would be a perfect way for me to consciously experience this state of the mind. And this way of living life. I also wanted to explore what it was like to actually teach myself a language from scratch; the sounds, sights, and physical act of learning to speak this language. I figured if I did this, I might get to observe in myself what actually happens in the brain when people learn a language. Not just the biological changes, mind you. The actual psychological processes which occur within one's consciousness. What kinds of skills do you need in order to learn a language? I wanted to see for myself. So have I discovered anything? To be perfectly frank, yes I have. A whole lot in fact. And to be honest, much of what I've discovered has very little to do with Greek per se and a whole lot more to do with how we learn in general. You see, it turns out we actually learn very little of what we believe we learn. Language wise or otherwise. Moreover, it turns out that "doing" is not the proof of learning experts tell us it is. Even when you can do things with variety afterwards. Practice Makes Perfect?Before I begin to explain all this though, I first need to tell you about a lecture I recently listened to. In it, an expert on learning languages spoke about how practicing a language is the only way to keep it. Of course, we have all been exposed to this idea in one form of another, be it through sports, times tables, dance; whatever. This time though something in what I heard this man say rang false. Which made me begin to question what place practice has in our life and more important, what we actually learn. For instance, if we need to keep practicing a skill in order to keep it, have we in fact learned any of this skill? What about if we retain this skill even after years have gone by. Is this kind of learning different than the need to keep practicing kind? And what happens to the things we think we have learned but later forget? Is it that we are doomed to forget most of what we learn? Is this the truth? Or is this kind of forgetting unnecessary? In the end, the more I tough about the idea of practice, the more I asked myself these kinds of questions. Which prompted me to do what I usually do when I ask myself questions; I began search my memory banks for related stories. For instance, what had I observed in others as far as learning a language? Forgetting RussianAt some point then, as I was mulling these ideas over in my head, I recalled a young couple I know who had adopted two children from Russia. This couple came to mind because the father had recently told me what seemed at the time to be a somewhat odd story. The story? As I mention, he and his wife had adopted two young children from Russia, a boy, two, and a girl, four; a brother and sister. At the time they to America, these children spoke only Russian. Fluently, of course. But only Russian. Now, a little more than a year later, these two children speak and understand English fairly well. Not too surprising really. We've all heard stories like this one. However, what is surprising is the fact that this man told me his children no longer understand let alone speak Russian. None at all. To such an extent in fact that he and his wife sometimes speak to each other in Russian in order to prevent the children from understanding what is being said. Can you imagine? The First of Many MysteriesHere then is one of the mysteries which has sparked this book. What happened to these two children and to their fluency in Russian? Did they literally forget what they had learned? Many experts would say they did. But did they? I was not sure. I then asked myself an even more serious question; exactly how much of what we believe we have learned have we really learned? Any of it at all? A little of it? None of it? And what about all things we do each and every day? Have we learned these things as anything other than a kind of temporary learning as opposed to a permanent skill? Something like the better golf swing we leave with after a lesson from the pro which within weeks seems to evaporate into thin air. In the end, I came to realize that these two kids had actually learned very little of what they had appeared to have learned. Moreover, that something else had happened to them which made them appear to understand and speak Russian. Something I have come to call, momentum learning. In a sense then, these kids were simply parroting Russian. And this is true despite the fact that they obviously did understand in a way different than parrots would. This then lead me to question learning in general? Does what I observed apply mainly to learning languages? Or does it apply to all learning? What did I find? It turns out that repeatedly doing something in a way in which we seem to have learned it while at the same time needing to practice it to keep it is one of the five main states we experience within the cycle of learning. Moreover, it turns out that this state, momentum learning, is a necessary and important step toward more the more permanent variety of learning. The learning to ride a bike kind of learning. But only if we can see it as such and know what to do next. Can this be? Can most of what we think we learn simply be that we are swimming in the momentum of a stream of practiced parroting? This idea is one of the main things we'll be exploring in this book. Why we forget most of what we are taught. Along with what is different about the more permanent kind of learning? And how we can make this the default in education. This last idea then; is there anything we could be doing differently to change the way we educate our children, is the real point of the book. Is there anything we can be doing to make what we teach our children emerge in them in ways in which they can focus more on creating a new and better world? The answer? There are ways. A lot of them in fact. Sound interesting? You can not begin to imagine. |

.